Translated by ChatGPT

中文版 https://youxiputao.com/article/26728

Since its initial reveal in 2020, the story of Black Myth: Wukong has been unfolding for four years. Two years before that, the idea took shape on a whiteboard in Game Science’s conference room. But how far back can we trace it? Perhaps to 2014, when Game Science was founded, or even earlier, to its predecessor, Dou Zhan Shen.

But if we go further back? Perhaps we should rewind to 2004, a time when online gaming was just beginning to rise.

01. "If You Fear Death, Do Not Enter This Door"

In 2004, in an internet café near Huazhong University of Science and Technology, a recent graduate was deeply engrossed in World of Warcraft, losing track of day and night. He would sleep in his rented room during the day and spend his nights gaming at the café. Out of savings but undeterred, he borrowed money from classmates, diving back into the world of Azeroth. This gaming enthusiast was named Feng Ji.

According to the usual plan, Feng should have been preparing for postgraduate exams after graduation, yet he often found himself questioning the purpose of studying and working. In contrast, the world of games was irresistible.

In 2005, Feng sent out over a dozen resumes and eventually landed a job as an MMO operations planner at a small game company in Shenzhen. His first task was to design an event within three months. This soon evolved into a routine of "small events constantly, and one major event monthly."

In the company, no one evaluated the effectiveness of these events, nor did anyone ask for Feng's insights into the game’s direction, let alone consider the needs of the players. Feng’s summary of his work was simple: don’t let the players get bored.

At the time, the industry buzzed with debates over whether Shi Yuzhu’s Zheng Tu(征途, Journey) had made a fortune and if its methods were ethical. Regardless, the discussions would inevitably end with the question: should we follow this approach too?

During his two-plus years as a planner, Feng experienced a profound sense of disillusionment and frustration. In 2007, he penned an article titled Who Murdered Our Games, unflinchingly exposing the chaos in the Chinese gaming industry. He bluntly declared, "This damn online gaming industry has given rise to a bunch of bastards like me." His searing questions in the article still resonate powerfully to this day.

Later, Feng stepped onto a larger stage, joining Tencent to lead the publishing and operations of the licensed game Xun Xian(寻仙, Seeking Immortals).

However, within Tencent, Xun Xian was not viewed favorably—in fact, it was a leftover project that others had passed on during product meetings. At the time, China’s MMO market was fiercely competitive, dominated by giants like World of Warcraft, Fantasy Westward Journey(梦幻西游), Chuan Qi(传奇, Legend), and Zheng Tu, making it seem almost impossible for Xun Xian to carve out a niche.

Yet Feng remained passionate. According to a Zhihu user named WaYne, who worked back-to-back with Feng, whenever WaYne pointed out flaws in Xun Xian—discussing gameplay, polish, or issues with the monetization model—Feng would counter and passionately praise the game’s unique art style.

In his early reports, Feng described Xun Xian as “Eastern, traditional, mythological, uniquely atmospheric, unconventional yet with potential.”

He continuously provided feedback to the developers, urging them to add more story and plot, cinematic effects, and immersive elements, even though these were not priorities in the online gaming landscape of the time.

Xun Xian

After 18 months working on Xun Xian, Feng’s opportunity finally arrived.

In 2008, MMOs were still a dominant force in the gaming industry. However, Tencent lacked a flagship title in this area and recognized the need for a game that could showcase its in-house development capabilities. Coinciding with the release of Tencent’s self-developed ATOMIC GAME ENGINE (also known internally as the May engine), the company decided to use this new engine to create a flagship title.

During the project’s initial planning phase, Feng presented a 2.5D MMORPG concept based on Journey to the West, which secured him a transfer opportunity as the lead planner for the project.

Years later, Lilith Games founder Wang Xinwen, while enthusiastically recommending Feng to Hero Games CEO Daniel, recalled that Tencent used to hold “33 meetings” where project leaders would present their products in competition. Wang noted that he would usually win awards whenever Feng was absent, but when Feng participated, the outcome was always unpredictable.

Feng Ji

At that time, Feng's project had the internal codename W-Game. Early on, it experimented with flashy effects and a cute, cartoonish art style—directions that were completely different from the mature Journey to the West theme it would later adopt. That changed with the arrival of Yang Qi and other team members.

Yang Qi, who had attended the China Academy of Art, was known for skipping classes frequently, and he didn't receive his degree upon graduation. In his senior year, he began working in online gaming, later moving through various small gaming companies and even starting his own venture, developing an MMO titled Shan Hai Zhi(山海志, Classic of Mountains and Seas).

Although these early projects weren’t particularly successful, they solidified Yang’s desire to create a large-scale game. The artistic quality of Shan Hai Zhi helped his team join Tencent, which Yang humorously described as "finding a big backer."

Before joining, a Tencent executive warned Yang that the company’s corporate environment could be "deep waters." Yang initially found it challenging to adjust, facing many procedural hurdles. He likened large, well-established companies to imperial enterprises, and would often work overtime, making covert optimizations to express his aesthetic vision in the project.

One Tencent employee from that period mentioned that Yang’s approach was to focus solely on crafting the most visually striking character designs, leaving other team members to handle the technical execution. He exuded a strong artist's temperament.

In a career talk in 2012, Yang admitted that he had once viewed domestic game planners as adversaries, believing most of them didn’t understand games and needed to be “taken down.” However, after meeting the W-Game team, he found them to be a "respectable" group—people truly striving to fulfill their dream of making games.

They began searching for a unique angle on the Journey to the West theme, eventually settling on the title Ta Xue Xi You(踏血西游, Bloodstained Journey to the West). Although the name was deemed too dark and received harsh criticism, leading to its abandonment, the team saw this as a positive sign—they had finally found the mature tone they sought for an adult-oriented MMO.

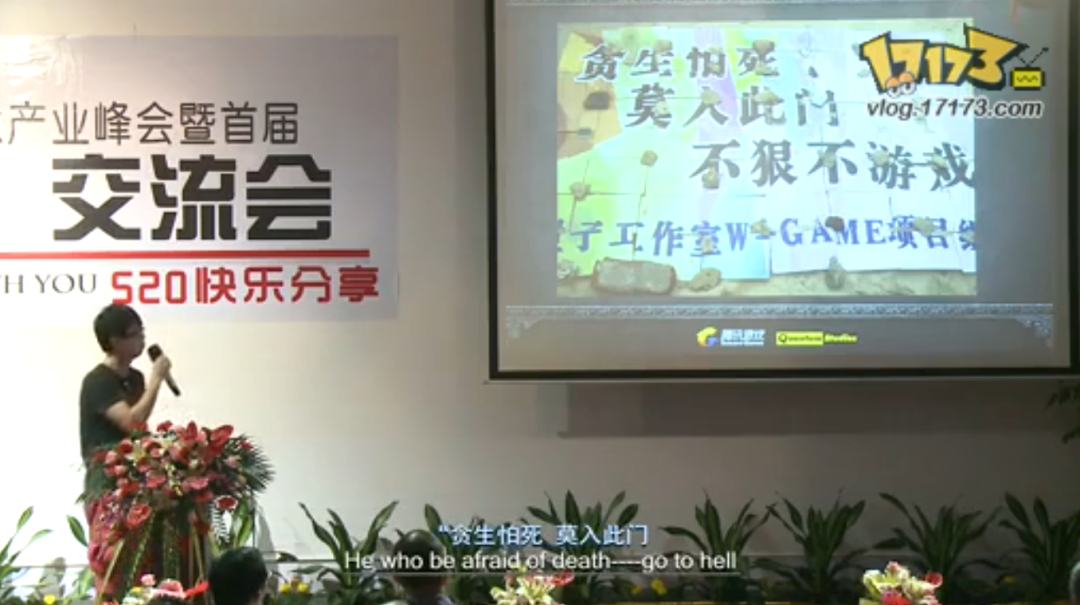

During the second project review meeting for W-Game, dozens of team members felt that if the project was destined to be challenging, they might as well face it head-on. The conference room was packed, buzzing with excitement, and they even created a puzzle with 13 bold characters: “If You Fear Death, Do Not Enter This Door; No Guts, No Game.”

Yet, in their lofty ambitions and high spirits, they likely never anticipated that the project’s development challenges would far exceed expectations, ultimately stretching on for five years.

02. Dou Zhan Shen

In December 2010, at Tencent's Game Carnival, W-Game made its official debut, named Dou Zhan Shen(斗战神, Asura). Feng, the lead planner, stood on stage alongside then-president of Tencent Games, Ren Yuxin, who compared Dou Zhan Shen to the culmination of hard-earned achievements in the gaming industry.

Tencent had high hopes for Dou Zhan Shen. The project was highly confidential in its early stages; according to Zhang Nu from the marketing department, many employees only knew a project was underway without knowing its name until the official announcement.

Dou Zhan Shen’s producer, Liu Dan, stated in an interview that this game represented the next generation of Tencent’s self-developed online games. Its technical preparation time was the longest in Tencent’s history, taking two to three times longer than usual projects, and its development team, initially fewer than 30 members, grew to nearly 200 at its peak—not including support teams.

Years later, Game Science’s technical director, former Dou Zhan Shen programmer Zhao Wenyong, revealed that although Dou Zhan Shen had performance targets, it was likely among the lowest priority in terms of KPI effectiveness. “The higher-ups were more focused on using it to build Tencent Games’ reputation and provided the team with substantial support and freedom,” he noted.

A team member from Dou Zhan Shen’s early days said the team had an almost obsessive drive to make something "unbelievably good," aspiring to create a masterpiece that would elevate the aesthetics of China’s gaming industry. “Inspiration usually struck at night. Whenever someone had an idea, we’d head straight to the meeting room for brainstorming, never mind the overtime—it felt like crafting an artwork that could raise the bar for everyone.”

In terms of marketing, Dou Zhan Shen adopted unprecedentedly bold promotional tactics for the industry.

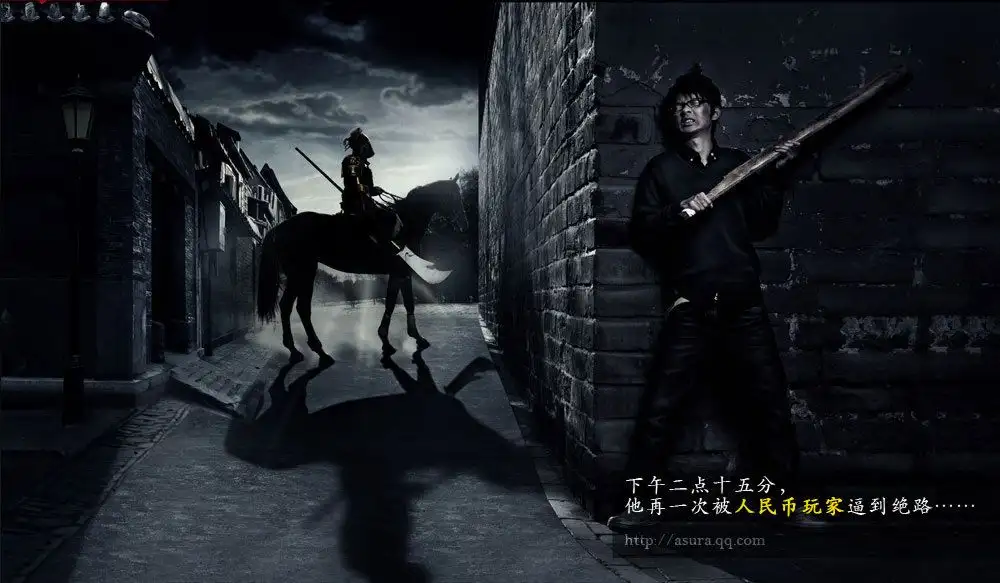

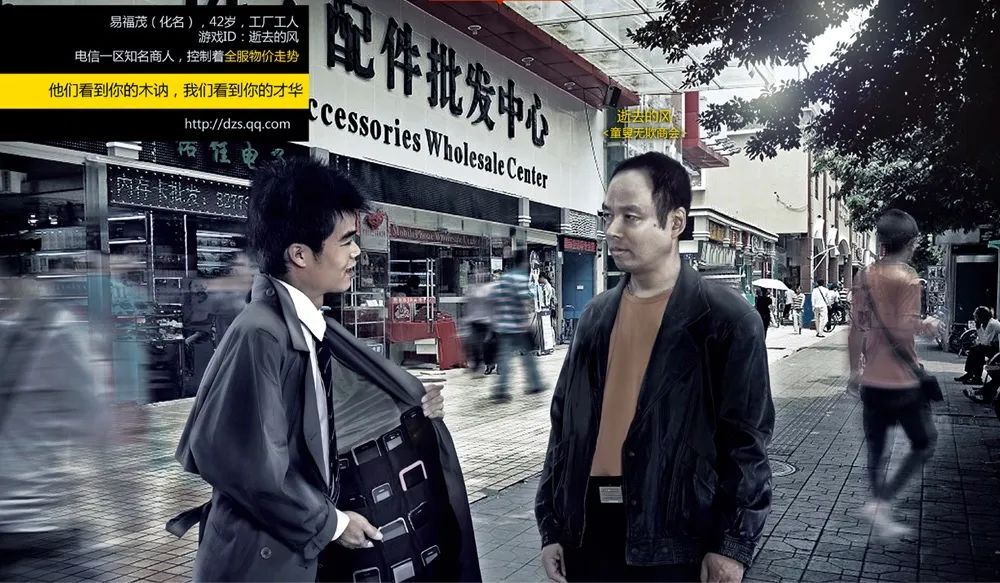

For example, it introduced a series of "static films" that, in retrospect, resembled teaser posters. Dou Zhan Shen's promotional images, themed "You’ve played games but never been happy," satirically critiqued the chaos of the online gaming industry.

This use of static film-inspired advertising soon became a trend among other game studios, although most attempts failed to capture the essence—Dou Zhan Shen’s unique brand of dark humor and relatability was hard to replicate. This creative insight can be credited to the brand manager Guangmang (Liu Zhipeng) and his cousin. During a family dinner that year, Guangmang’s cousin boasted about his prowess in gaming, only to be dismissed by the older relatives: “Sure, sure, you’re great—now eat.” His cousin muttered, “You guys just don’t get it.”

This observation highlighted the frustration gamers feel in society, where their achievements are often overlooked. It inspired the creation of posters bearing lines like “They see your ordinary self; we see your greatness” and “You wouldn’t understand my joy.”

These inventive ideas touched every aspect of Dou Zhan Shen’s marketing. In 2011, while most Chinese games followed grandiose or overly tacky promotional approaches, Dou Zhan Shen embraced April Fool’s Day pranks with a mix of true and false announcements, stirring excitement among fans.

They even hinted at a single-player mode, and just before the game’s open beta, they released a small offline version so players could get a quick taste of the action.

From a gameplay perspective, Dou Zhan Shen introduced several bold and unconventional changes.

In terms of monetization, Liu Dan was clear about wanting to break from traditional online games and avoid unlimited item purchases. He emphasized that players’ enjoyment should not be rooted in spending money. “A game’s fun should come from the game itself, not from how much you pay to play,” he stated.

On the content side, Dou Zhan Shen spared no effort, filling the first three story chapters with cinematic sequences, each ending with an original music video—a bold move in an era before the concept of “content-driven games” even existed.

In addition, the team brought in Jin Hezai, author of Monkey King, to serve as the world-building architect. They also collaborated with The Third Floor, the visual effects studio behind Avatar, and China’s Original Force Animation to produce high-quality CG scenes. According to Yang Qi, in one scene depicting an army of demons charging forward, every creature was uniquely designed, costing a total of 8 million RMB.

Such dedication to content was evident throughout the project: they partnered with the Harry Potter voiceover team, secured music rights from the classic 1986 Journey to the West TV series, and collaborated with musicians Eason Chan and Lin Xi for original songs.

In terms of gameplay, they introduced the “Combat 2.0” concept, aiming to elevate combat in Chinese online games to next-gen quality. They wanted each class to feel like a distinct game, and in Tencent’s 2012 annual gaming conference, Feng even showcased gamepad controls, underscoring the team’s commitment to refining combat mechanics.

They even pushed the programming team to make arrow shots missable and dodgeable, similar to an FPS experience—a remarkable feat for an MMO. The lead programmer joked in interviews that he often felt driven to jump off Tencent’s 29th floor from the pressure of these demands.

Ideas continued to flow throughout development. In 2010, a colleague suggested in an internal forum that a Journey to the West game should incorporate transformation mechanics, enabling players to turn into a bird to fly across cliffs or to morph into bosses of corresponding levels. Feng noted down the suggestion and promised to present a “72 Transformations” design by the second quarter.

Despite the overwhelming technical challenges and the ambitious concepts that seemed unimaginable at the time, the team overcame numerous hurdles. In 2011, the Dou Zhan Shen team won Tencent’s internal award for best technical breakthrough, and there were even rumors that Riot Games wanted to collaborate on an MMO using the AGE engine.

Their efforts paid off: from the early testing rounds starting in 2011, Dou Zhan Shen earned outstanding feedback, repeatedly setting records for Tencent’s self-developed games. In the first round of testing, activation rates reached 99.7%, with over 85% of players highly satisfied. Nearly 50% of players logged in almost daily during the first month. By the 2013 open beta, the game’s peak concurrent users (PCU) exceeded 600,000, marking one of the best open-beta performances for MMOs in China at the time.

The attention was staggering. According to an early team member, whenever they released a bit of promotional material, top gaming sites like 17173 and Duowan would immediately reserve their headline space.

However, just as everyone expected the game to maintain its success post-launch, Dou Zhan Shen’s metrics suddenly plummeted.

03 After Lady White Bone, there is no more Journey to the West.

In the team’s initial vision, Dou Zhan Shen was meant to be a game where players would continuously tackle dungeon challenges. As a 2.5D MMORPG with top-down view, diverse class designs, and complex equipment systems, it drew heavily from Diablo.

However, during later testing phases, the team discovered a critical flaw: small four-player dungeons didn’t foster the social bonds necessary for a long-term MMORPG. In response, they linked the sect system to dungeons and added open-world challenges where players, as sect groups, would compete for resources. Unfortunately, many players disliked the intense social pressure that came with such interactions.

This created a challenging dynamic: the game’s content burned out quickly, yet the intense gameplay couldn’t alleviate long lulls, only adding to players’ fatigue.

Conflicts surfaced, and players began to leave. In early 2014, Feng appeared frequently in player communities, personally addressing questions and concerns.

While his responses were witty and relatable, subtle anxiety could be read between the lines. Discussion topics revealed that Dou Zhan Shen had, in many ways, become another typical MMORPG, struggling with the usual suspects: monetization, class balance, drop rates, bots, exploits, and “grind-to-win” pressures.

In earlier interviews, the team had stated that they originally planned for eight game chapters, not just the five released. The first few chapters were only intended as a prologue to a grander narrative. However, in the final version, endgame content like Heaven and Hell dungeons was released much earlier than intended. Yang lamented on social media that certain planned content, like the Bibotan dungeon, would remain forever unfinished.

The development hurdles Dou Zhan Shen faced remain partially mysterious, but one factor mentioned by team members was religious censorship, which constrained some story elements.

Perhaps the toughest challenge was production capacity. The first three chapters, widely praised by players, took over three years to complete. As the fourth and fifth chapters rolled out, the storyline began to lose its original momentum, and certain signature features, like the cinematic cutscenes with original MVs, stopped abruptly after the Lady White Bone chapter. Even voiceovers started to decline.

Although the team pledged multiple times to fill in these gaps, what actually emerged were filler systems and gameplay adjustments, leaving players with the bittersweet sentiment, “After Lady White Bone, there is no more Journey to the West.”

In Quantum Studio’s 2013 annual meeting, the Dou Zhan Shen team filmed a humorous music video titled Let’s Just Leave It at That. One line went, “Five years of effort, but still not a match for Blade & Soul for a single day.”

Dou Zhan Shen was up against more than just Blade & Soul, however.

After five years of development, the gaming landscape had transformed, with PC gaming losing ground. A former Tencent employee recalled that, back then, a few million RMB in annual revenue was considered significant, but with the mobile gaming wave, daily revenues could reach hundreds of thousands or even millions.

In one industry event, Liu Dan remarked that PC games wouldn’t die but admitted it had become a sunset industry. Meanwhile, at the adjacent Lightspeed Studios, developers were frantically pushing out WeFly, a mobile game that, with support from WeChat, was pulling in staggering revenue. In comparison, Dou Zhan Shen’s future looked grim.

Around Lunar New Year in 2014, Dou Zhan Shen, feeling the squeeze of the times, increased its monetization efforts and announced plans for spin-off browser and mobile games under the same IP.

In retrospect, tech director Zhao Wenyong observed, “Tencent’s upper management had good intentions, but Dou Zhan Shen’s failure still stung. After the triple disaster of updates to Demon City (Chapter Five), it was no longer Tencent’s darling, and the increase in microtransactions was only natural.”

In April 2014, Dou Zhan Shen launched a video series called I Love to Critique Designers, where designers and the producer appeared on screen to face player complaints. To this day, Feng’s appearance in one of these viral videos remains one of his most well-known public appearances.

In it, he’s mockingly slapped, bruised, and hit with ramen bowls by disgruntled players, his self-deprecation doing little to mask a sense of helplessness.

Two months after the video was released, Feng, Yang, and five other core members of the Dou Zhan Shen team left Tencent to form Game Science. The wheel of fate was beginning to turn once more.

04 Copycat

Before founding Game Science, Feng had already decided on his next project: a mobile game.

At the time, the only mobile game that truly captivated him was Dao Ta Chuan Qi(刀塔传奇,Dota Legends) — the groundbreaking game created by Wang Xinwen after he left Tencent. In an interview with IGN China, Feng shared that the mobile gaming boom was his primary motivation for leaving Tencent.

However, his colleague Yang Qi had a different perspective. He couldn’t let go of the immersive quality of larger games, believing only console-level experiences could create true engagement. How could mobile games, with such limited screen real estate, deliver high-quality visuals and experiences?

But Feng managed to persuade him: “Let’s make a quick hit to get some revenue first; we need to survive before we thrive.” They decided to develop a game similar to Dao Ta Chuan Qi.

Feng’s vision also convinced Zhao Wenyong and Jiang Baicun, who hadn’t left Tencent initially but joined Game Science after receiving Feng’s call.

Jiang, a former Dou Zhan Shen designer and now lead designer of Black Myth: Wukong, recalled that he had bought a PS3 because of Feng’s recommendation to play God of War. So, when he heard that Feng had started his own company, he had a feeling Feng would eventually reach out.

Most of the Game Science team initially had limited knowledge of mobile game design, so they poured time into dissecting Dao Ta Chuan Qi’s mechanics. Jiang even spent thousands of yuan on in-game purchases to understand its appeal. Within a week, they produced a prototype for their new game, Bai Jiang Xing(百将行,Hundred Generals).

In 2015, during NetEase’s annual “520” game showcase, Bai Jiang Xing, now published by NetEase, debuted with the tagline: “The Ultimate Action Card Game.” Much of the attention surrounding the game was drawn by its team’s legacy — many wondered what kind of magic a former Tencent team collaborating with NetEase would bring.

Despite being a mobile game, Bai Jiang Xing bore the creative aesthetic of Feng and his team: bold and imaginative.

The game’s theme was based on Romance of the Three Kingdoms, sharing a conceptual thread with Dou Zhan Shen. In a GameGrapes interview, Feng explained that regardless of the genre, they would always prioritize world-building, drawing on the soul of characters and relationships rather than aesthetics alone.

He elaborated, “Romance of the Three Kingdoms was already a re-imagined work by Luo Guanzhong, blending popular aesthetics of the Ming dynasty with supernatural elements. We wanted to maintain this spirit of imagination.”

Their characters in Bai Jiang Xing reflected this creative license. Guan Yu, the hero known for his loyalty and valor, was portrayed as a dragon, while Cao Ren, typically depicted in heavy armor, was reimagined as a fortress-like robot. Some characters even took on monstrous forms. Yang later explained that since this was a mobile game, they felt freer to incorporate playful, fantastical elements.

When asked why they gravitated toward classic adaptations, Feng explained that while they considered original stories, China has a wealth of enduring classics. “There’s a saying: Journey to the West is China’s Lord of the Rings, while Romance of the Three Kingdoms is China’s Game of Thrones,” he said. “These stories are powerful classics. Our biggest motivation is to let them shine anew. That’s why we started with Journey to the West, then moved to Three Kingdoms, and perhaps will return to Journey to the West in the future.”

Yang echoed this sentiment more directly on social media, criticizing the lack of confidence he observed in the industry. “Our ‘lack of self-confidence’ is evident in endless debates about what’s worth doing based on how others approach things. It’s a strange form of self-doubt for creators to have to justify even their choice of themes.”

The game’s artistic direction did attract some players, with fans drawn to its unique character designs. Zlong Game CEO Wang Yi even praised Dou Zhan Shen and Bai Jiang Xing for breaking the mold of conventional design in China’s game industry.

However, Bai Jiang Xing couldn’t escape the gameplay limitations of its inspiration. During testing, Chuapp, a gaming news site, published a review of Bai Jiang Xing, pointing out some shortcomings. Feng responded by reaching out and submitting a developer’s statement to Chuapp, explaining his design rationale.

Nevertheless, while Bai Jiang Xing attracted 500,000 players in its first month, retention dropped sharply, and its total player count over the year barely reached 800,000.

Rumors circulated that NetEase hadn’t rated the game highly internally, and while it did receive standard promotional support and a virtual Guan Yu mascot, its overall marketing budget was modest.

Two years later, in another Chuapp interview, Feng admitted that Bai Jiang Xing had “died a worthy death.” It was, as he put it, burdened by the inherent “original sin” of being a copycat, which made it feel “low-brow.”

Still, for a startup, Bai Jiang Xing provided Game Science with a solid revenue stream, enabling the company to keep going. So, what would they make next?

As Bai Jiang Xing wrapped up, Yang again proposed creating a console-quality single-player game. Although there were few vocal objections, everyone knew that such a project would be incredibly costly and high-risk for a company that was only two years old.

In the end, Yang’s proposal was shelved once more.

05 Creating Games that Move Us

After the release of Bai Jiang Xing, Game Science held a retrospective meeting. The conclusion drawn was that they should not simply cater to the market, but rather create things they genuinely loved. Around the same time, Game Science launched its official website, introducing their product philosophy: first and foremost, it’s about moving oneself.

In 2016, Feng took a few sheets of paper filled with questions and traveled to Wuhan to meet a MOD creator known as "Monsk Daiting."

He was the author of the Desert Storm map in *StarCraft II*, which Feng had been deeply immersed in for a long time. During several hours of conversation with Monsk Daiting, he asked about various potential issues with Desert Storm and drew a wealth of optimization insights from their discussion, which ultimately inspired the development of Art of War: Red Tides (战争艺术:赤潮).

In simple terms, while Red Tides emphasizes the RTS aspect through its English title, it significantly simplifies operations to suit mobile experiences.

Players only need to strategize during a 12-second preparation period each turn and then release commander skills based on the battlefield situation. Each game round is kept to about 10 minutes.

However, this does not mean that Red Tides is just a simplistic game; it retains intricate strategic elements. The diversity and complexity of units require players to have a deep understanding of values and attributes. Many player actions also lack immediate feedback, akin to chess, necessitating a delayed sense of satisfaction.

Nonetheless, once players become familiar with the game, those who enjoy it tend to get highly engrossed.

The CEO of Hero Games, Wu Dan (Daniel), initially joined Game Science due to Wang Xinwen’s strong recommendation. Although he was quickly impressed by Feng’s capabilities and persuaded him to accept investment from Hero Games, he actually didn’t understand how to play Art of War: Red Tides. However, after returning, he unconsciously spent over 300 hours immersed in the game.

In 2017, when Art of War: Red Tides debuted on iOS, it achieved astonishing success: recommended by the App Store in 154 countries and regions, with nine placements on the App Store homepage; it ranked third in the iOS free game charts, only behind Honor of Kings (王者荣耀) and Happy Landlord by Tencent(欢乐斗地主·腾讯).

By year’s end, Red Tides was the only Chinese game to be included in Apple's annual recommendations, also becoming the best iPad game in the Chinese market. At the same time, Cook experienced the product during his visit to Hero Games in China. From this point on, Game Science truly began to gain recognition.

Additionally, it was more than just a mobile game. In fact, Red Tides had earlier launched on Steam.

During its initial testing phase, without any marketing, it garnered an impressive 87% positive reviews, with around 400,000 users, even topping the Steam free game charts.

It’s worth noting that back then, Steam had a stringent approval mechanism, and not every game could simply be listed. This experience left Feng feeling surreal—there were so many others in the world who shared his interests, and this group included some of the most discerning gamers in the market.

Developing a PC version also provided some comfort to the team. Lan Wei Yi, the operation director at Game Science, noted that from the regret of Bai Jiang Xing, they clearly sensed the team's strong desire to achieve PC-level graphics on mobile. He often heard Feng say that if they had used Unreal or 3D technology, the product would have turned out quite differently.

Sometimes, these obsessions became more pronounced.

Whether deliberate or subconsciously, while Art of War: Red Tides doesn’t directly relate to the Journey to the West theme, it still bears many traces of Dou Zhan Shen.

For instance, the game’s base is called "Lingyun" (灵蕴), a core concept originally from Dou Zhan Shen; another unit is named "Lady White Bone" ; not to mention that the design of the demon units is rich with Journey to the West influences, including a skill called Flower and Fruit Mountain (花果山) that transforms units into monkeys.

Lan Wei Yi recalled that towards the end of Art of War: Red Tides’s development, a recurring sentiment among the team was a desire to create an immersive "single-player game." However, more accurately, they felt they could only create another mobile game, albeit one that might aspire to achieve PC-level quality.

Only Yang could not suppress his restlessness. That year, he discovered he had pharyngitis, which prompted him to reassess his state. He realized that he had not invested much emotion into Art of War: Red Tides; many designs felt like mere task completions, and the company’s slogan, "Only create games that move us," seemed to have not been genuinely realized.

Since the time of Dou Zhan Shen, he had maintained that a person's peak creative age might only last about ten years, and creating a large-scale game could consume up to five of those years—leaving little room for error. Thus, he approached Feng again.

In the end, Yang faced his third failure. Feng persuaded him to create another mobile game. According to the plan, they were going to develop a quick-profit RPG+SLG project. However, shortly thereafter, things took an unexpected turn.

06 Black Myth: Wukong

On the tenth day of the first lunar month in 2018, a meeting was held to determine the future direction of the company. That evening, after returning to Shenzhen, Feng called an impromptu partner meeting.

During the meeting, they selected a development path for the next few years: retain the mobile game team and assign a few members to prepare for research and development of a single-player action game. This was a middle-ground approach.

Each person proposed the themes they wanted to pursue. Yang expressed a strong desire to create something set in the Beiyang Warlord era, admiring Jiang Wen's visual storytelling. "On one side, there are black ships and cannons, on the other, knives and guns, with grand themes of heroism, intertwined with delicate and touching stories. When the plot gets dull, a puff of smoke brings forth all kinds of fantastical scenes."

In the end, perhaps due to unresolved internal conflicts, they unanimously agreed to pursue the story of the monkey that never reached Ling Mountain. Thus, Black Myth: Wukong was initiated, with the project codename B1, representing the first product in the Black Myth series.

What drove Feng to suddenly change his mind? Perhaps even he couldn’t pinpoint the reason.

In interviews with media such as Chuapp, Feng provided various explanations. For instance, he mentioned that Yang’s persistence made him waver. During a dinner, Yang said seriously, "You can always find a reason not to start this project, but if we keep waiting, it might never begin... In fact, the company's appeal to me is gradually decreasing." Additionally, Feng noted that during the process of initiating a new project, he found himself growing restless. Of course, these reasons were not mutually exclusive.

Later, after the first reveal of Black Myth: Wukong, Lan Wei Yi recalled the project's inception. While preparing data for the 2017 annual meeting, they suddenly realized that the number of users in the Steam Chinese market had surpassed that of the United States, making it the largest. The Chinese single-player game market was akin to the Chinese film market in 2002, waiting for a film like Hero(英雄) to usher in a blockbuster era. At this moment, developing a single-player game might no longer be a thankless and costly endeavor.

Feng also believed that developing both PC and mobile games was not contradictory; to some extent, it represented a more sustainable development approach. Although Yang remarked that the decision to create a single-player game expanded the company's potential pitfalls from 99 to 100, it was undeniable that he was the most passionate member of the team. After designating a specific project area in their Shenzhen office, he moved his workstation there the next day and even personally designed the decor of the new office in Hangzhou, traveling across the country for project research.

However, once the push for development formally began, numerous problems arose.

Initially, everyone had a general consensus on the game’s direction: they aimed to create an action game with a strong sense of enemy pressure, intricate level design, and a mysterious narrative style. But what direction should the style take? Should it be like Monster Hunter, Dark Souls, or God of War?

It's important to note that this discussion wasn't about specific game types but rather the feelings they wanted to convey to players. For example, God of War focuses on action performance, while Dark Souls emphasizes clever level design and character progression.

Perhaps due to the experiences from the previous two projects, the team came to a clearer understanding after discussion. They abandoned the idea of directly mimicking any specific product and began consciously differentiating themselves from established giants. Internally, they summarized one of their development philosophies as "A Hero," which is an acronym for a series of keywords, such as Addictive Gameplay, emphasizing excellent growth experiences rather than mere numerical progression.

They sought to create a design language for Black Myth: Wukong, such as using a bronze head and iron arms to replace traditional weapon blocking mechanics; instead of crouching to stealthily navigate through bushes, players would transform into a golden cicada, blending with plants. They also chose to adopt a chapter-based level design to reflect the lengthy journey of Journey to the West, rather than enforcing the level structure typical of the soul-like games Feng was passionate about.

Beyond design, technical challenges required significant time to overcome. To present higher quality graphics and a cohesive open world, Black Myth: Wukong initially selected the UE4 engine for development (later transitioning to UE5). This was a new domain for the team, requiring them to start from scratch, studying documentation and familiarizing themselves with its features.

In the early demo, character expressions were not natural, and there were frequent clipping issues during animations. Feng repeatedly expressed a desire for talented technical artists; he envied the real-time animation details in The Last of Us Part II—the way characters smoothly interacted with their environment, such as running up to a table to pick up a cup, maintaining fluidity from any angle. However, achieving such smooth and visually appealing animations took them about two to three months.

During the initial research phase, they formed a team of seven or eight people, starting work on the Flower-Fruit Mountain level, depicting the vast scene of ascending the mountain and ultimately battling celestial soldiers in the clouds.

However, by the end of 2018, the preliminary level could only be considered partially completed and far from satisfactory. Yang felt that relying solely on his own experience and knowledge at the time, it was impossible to reach the quality of God of War.

As a result, in 2019, after expanding the team to 20 members, they decided to skip Flower-Fruit Mountain and instead focus on a simpler level that could effectively convey the game’s final quality, which they named "Black Wind Mountain." Later, in an interview with Xinhua News Agency, Feng remarked that after completing the fire blade wolf level in "Black Wind Mountain," they finally felt they had grasped some principles of character creation.

However, the specifications for developing a large-scale single-player game still posed objective challenges in terms of production capacity. Yang stated at an event that in the past, while working on mobile games, the requirement was to submit two characters per week, but for Black Myth: Wukong, they could only require one character every two months, and there were over 160 characters to develop.

To create high-quality models, Yang wanted to leverage outsourcing. He noted that in Black Myth: Wukong, the cost of creating a flower pot or a rockery exceeded that of an actual pine tree; constructing a large building could cost over a hundred thousand yuan, nearly enough to build a structure in a small town. This reflected their pursuit of detail. "Once, we asked an outsourcing team to sculpt a window, and they said something so simple shouldn't be done by them. But when they received it, they found the window had a painting of the Eight Immortals crossing the sea."

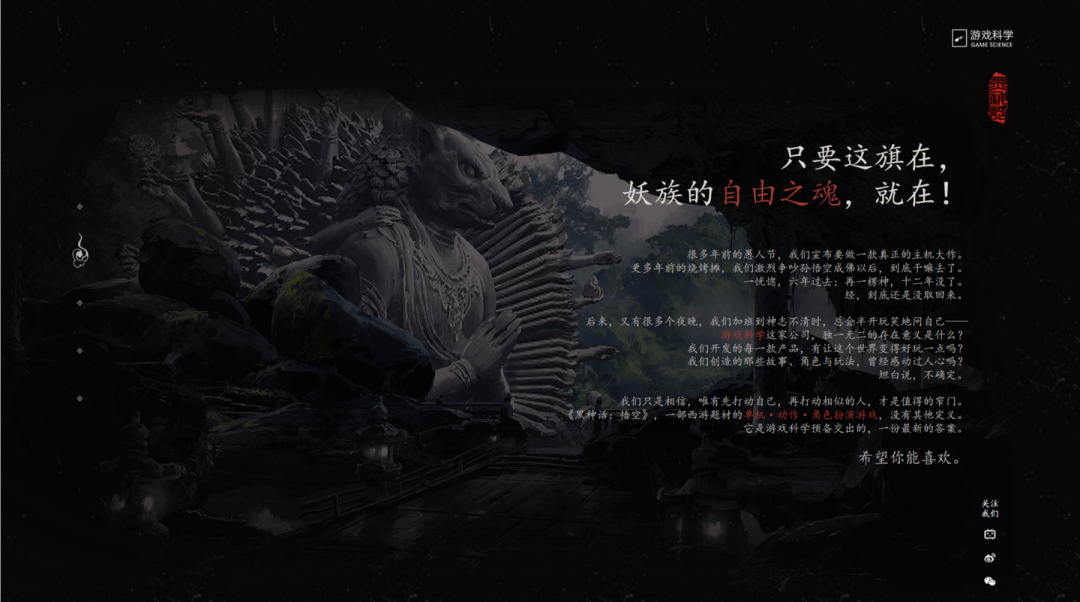

Thus, for Game Science, bringing Black Myth: Wukong to fruition could not solely rely on the efforts of a small team of a few dozen people. In 2020, to attract more talented individuals, they decided to release a gameplay teaser to draw in like-minded friends. This decision would lead the entire Chinese gaming industry to eagerly anticipate August 20th for the next four years.

07 After Lady White Bone, Walking the Journey to the West Again

The entire trailer was edited by Feng, who also designed the dialogue. Since April 2020, he called everyone into the meeting room every two weeks to watch the new version of the trailer. Eventually, the video was locked at 13 minutes long, which is a length that very few games reveal during their first exposure.

After the finished product was out, Feng sent it to Yang, who replied that the best trailer in Chinese gaming was finally no longer that CG from "Dou Zhan Shen." He bet that the trailer's view count would reach 3 million, while Feng was a bit taken aback, thinking that reaching 500,000 would be good enough.

In the end, the result exceeded everyone's expectations. As the final credits for "After Lady White Bone, Walking the Journey to the West Again" rolled, Game Science and Black Myth: Wukong exploded: Yang’s Weibo received over 100,000 shares; Alibaba Cloud customer service called Feng to say the official website had run out of traffic; friends on Bilibili told them that the trailer's view count growth was even more staggering than the push for "Hou Lang" throughout the first half of the year.

After that, everyone should know what happened. On that day, all Chinese gamers shouted that their long-held dreams had been realized by others; online, people celebrated and discussed whether the spring of domestic 3A games had finally arrived. Major companies began to follow suit, with investment, distribution, and business cooperation offers flooding in, and even headhunters from various companies were poised to act. Enthusiastic players directly ran to Game Science’s office to make pilgrimage.

In the face of this unexpected surge in attention, the reactions of Feng and Yang seemed not inflated, but rather filled with anxiety and concern.

That afternoon, Feng held a company-wide meeting, first affirming the trailer's success, and then suddenly presenting dozens of negative reviews. He hoped to cool down the excitement this way. Yang then asked everyone to maintain the work pace from the day before, warning that whether becoming lazy or overly eager, neither was a good thing.

In later public statements, Feng always used the word "luck" when discussing the initial trailer release. He believed the team had benefited from a technological boom, hitting the right emotional note for players at the right time.

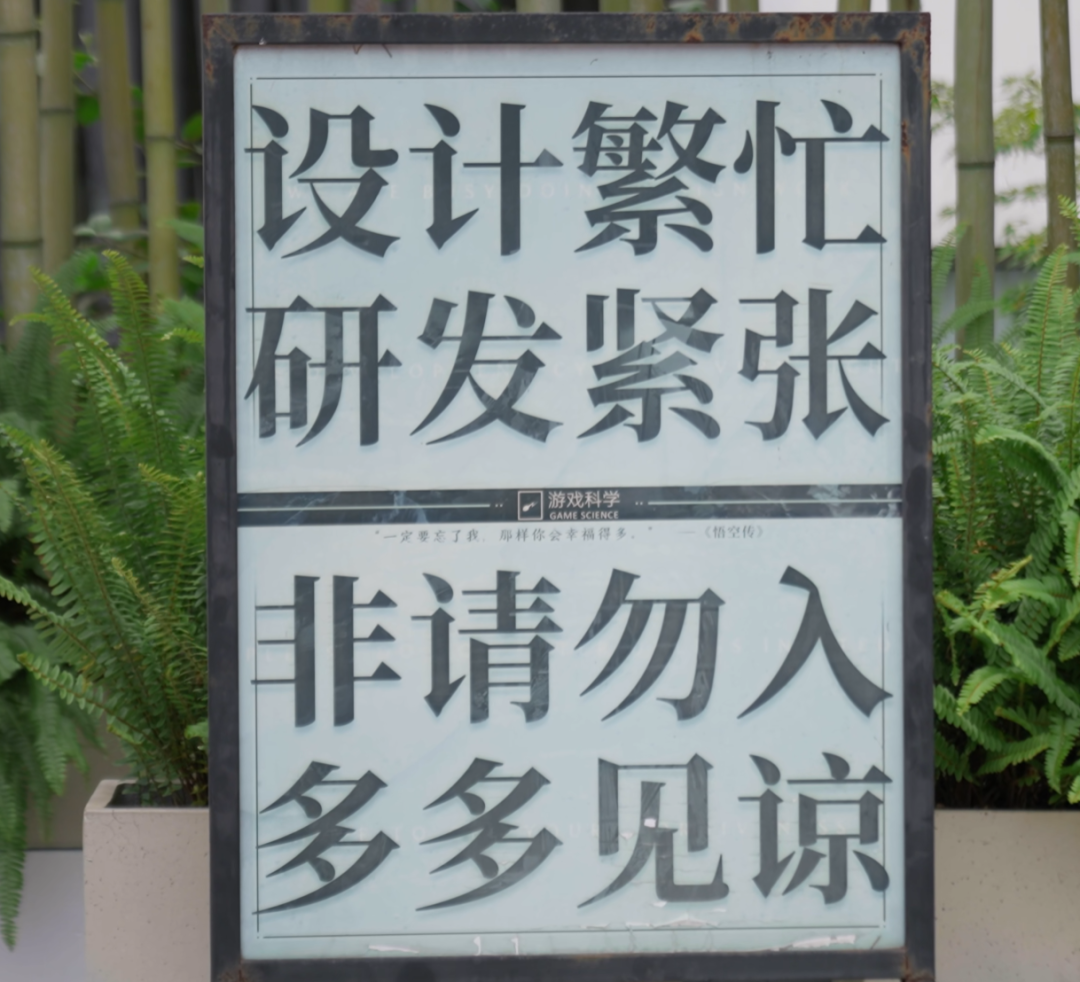

However, for Game Science, being in the spotlight often comes with immense pressure. A barrage of gossip and speculation about Black Myth: Wukong and the team surrounded them.

Feng's past statements were constantly dug up, as well as the inappropriate job ads and male-centric offensive expressions... Many labeled him and Game Science as gender discriminatory.

From that point on, discussions surrounding diversity and inclusivity continued until the launch of Black Myth: Wukong, sparking widespread discussions globally. Many well-known foreign media outlets criticized Game Science in public articles regarding this issue.

Additionally, every now and then, there would be voices predicting the failure of Black Myth: Wukong. In the year following the game’s first exposure, rumors circulated about the departures of combat designers and 3D artists, with comments claiming Game Science was undergoing internal strife. Although these topics eventually concluded with denials from the parties involved, it was evident that Black Myth: Wukong had become the focal point of the Chinese gaming industry.

The game even possessed significant crossover potential. In an online debate competition held by the Chinese Debate Network in 2023, the topic "Does the current Chinese gaming industry need Honkai: Star Rail or Black Myth: Wukong more?" was used as a debate prompt.

For a once-obscure small team, suddenly standing in the spotlight must have been a terrifying experience.

In the following years, aside from reporting on project progress during the annual 820 and Spring Festival events, they reduced their public presence. Feng even set his Weibo to be visible only every six months, trying to manage player expectations and avoid losing control over the game.

On the 820 day in 2021, Black Myth: Wukong released a high-quality trailer showcasing the UE5 demonstration, highlighting the team’s mastery of UE5 features, the snow physics effects, and the movement simulation of the Chinese dragon, all of which were commendable. Yet Feng stated, "Video montages, do not trust them. Let’s keep our heads down and forge ahead."

Feng recalled that after the game's first exposure, his sleep quality deteriorated, and he used 16 words to describe his state: "treading cautiously, walking on thin ice, unworthy of the position, feigning calm."

Even a year later, he still occasionally felt a sense of unreality, wondering "why are so many people paying attention?" He understood that Black Myth: Wukong still had many shortcomings, and even released several bug videos on the preview station to express that these unfortunate issues were part of the daily development routine.

Despite the self-deprecation, the production of Black Myth: Wukong in these years could be considered to have progressed steadily. In 2021, Game Science accepted an investment from Tencent for a 5% stake. Feng stated that he held no animosity towards Tencent, and through cooperation, they could better master the UE5 engine. By mid-2021, they had successfully recruited many technical talents, increasing the team size to nearly 90 people. Later, they collaborated with Nvidia to further enhance visual performance.

At the same time, Game Science remained pragmatic. After thorough investigation, the investment from Tencent was actually transferred in one lump sum, but Game Science was still cautious in spending; they even scrapped a core mobile game project that had been validated in order to focus as much energy as possible on Black Myth: Wukong.

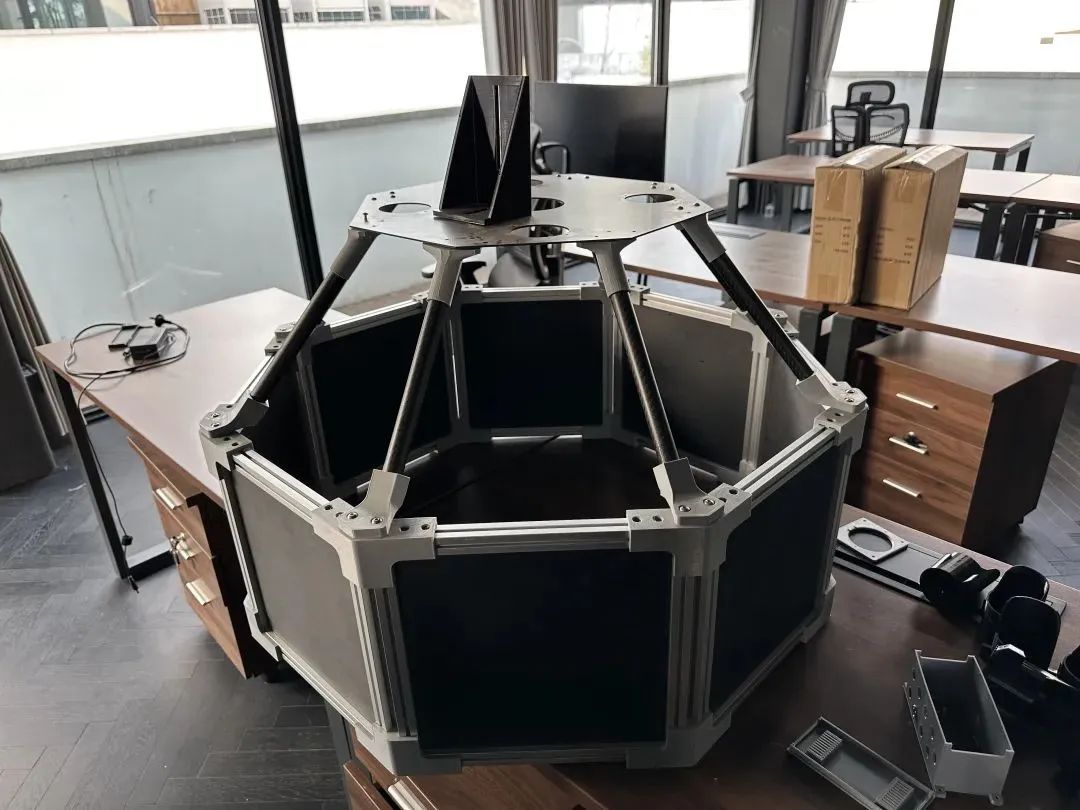

Pragmatism permeated the development process. When preparing for motion capture production, the team once bought a data connection cable from Xianyu, an industrial lens from Taobao, and disassembled the positioning device from HTC Vive, creating a rod by plugging in a power bank, ultimately achieving results equivalent to a professional solution worth hundreds of thousands of yuan at a cost of over ten thousand.

Even more outrageous was that another machine for scanning surface vegetation was simply assembled using parts generated by a 3D printer worth over 1,500 yuan. When facing an interview with Xinhua News Agency, Feng stated that they were striving to become a group of pragmatic idealists.

On August 20, 2022, Black Myth: Wukong released a segment of live-action dialogue. This video was met with much controversy; some felt that the quality differed significantly from the fighting scenes of the previous two years, potentially exposing various issues within the project. Others argued that the overly beautiful demonstrations from the previous two years made this segment of dialogue feel genuinely feasible for the project.

Regardless, Yang stated that this segment was an attempt at content they were not familiar with—some themes they were not good at nine years ago and still struggled with now.

He referred to the "Lady White Bone" in Dou Zhan Shen. Years ago, Yang had complained to his colleagues that the divine and demonic themes should tell grand tales, but instead, they were filled with petty romances, feeling shameless about not liking the romantic tropes. However, he now felt that after years of reflection, he might understand it a bit more.

As Yang mentioned, fate is like an intricate web of opportunities intertwining wildly.

WaYne, upon seeing the trailer for Black Myth: Wukong, was most moved not by the moment when the Ruyi Jingu Bang appeared, but by the instant when the Land God emerged from the ground. He recalled that in the second half of 2007, Feng had told him multiple times about wanting to include this scene in Xun Xian even gesturing wildly and pointing to his hairline.

Likewise, the promotional style of Black Myth: Wukong inherited from Dou Zhan Shen has transformed from a satire of online games into an expression filled with sentimentality and elements of the Journey to the West.

Notably, the first brand manager of Dou Zhan Shen, Guangmang, has now become the general manager of Tencent Interactive Entertainment's Content Ecology Department. In the Spring Festival short film "Stage Results" in 2022, he made a guest appearance as a character. Additionally, the virtual anchor Xing Tong under Tencent Interactive Entertainment’s Content Ecology Department recently held a live stream and offered thousands of copies of Black Myth: Wukong as prizes.

After more than a decade of twists and turns, some people and things seem to remain unchanged.

Last year, after "Black Myth: Wukong" announced its scheduled release date, Feng posted on Weibo. He said that for years, he had lived in a state of excessive exposure and self-doubt, and being able to garner such immense attention was truly fortunate.

But I think he must have experienced similar feelings long ago. In his Weibo post, he stated that what Black Myth: Wukong could do this time was to face user expectations directly, as this was their destiny.

08 Facing Destiny, Finally Reaching the Ling Mountain

Black Myth: Wukong landed smoothly. It did not disappoint the expectations of many, receiving a 96% approval rating and breaking over 2.2 million concurrent players on Steam, with mainstream media clamoring to report on it. It is safe to say that it has created a new history for the Chinese gaming industry.

While writing this article, I tried to contact people from Game Science's past, but most declined. Some said that the reason for their avoidance was a simple desire to protect it, fearing that their expressions might inadvertently shatter it.

However, if you browse through social media, you'll find countless game developers expressing their feelings, calling Game Science the craziest dreamers. This includes not only those pursuing their dreams in the independent and single-player game sectors but also many standout figures in commercial gaming, along with several of their former colleagues.

Before the game’s release, Daniel posted on social media: "Many people have asked me how I invested in 'Black Myth: Wukong,' but I actually can’t answer that, because the methodology here is simple to the point of being unremarkable: it’s all up to people... as long as the people are right."

Indeed, while reviewing the materials from Feng and Yang, I found that many ideas had already been seeded long before they even entered the industry: a group of young people coming together solely to realize the game dream in their hearts. This simple idea, unchanged even after more than a decade, still resonates.

However, after over ten years of hardships, some things have indeed changed. In an interview with Xinhua News Agency, Feng mentioned that he is no longer as angry as he was when he wrote articles in the past; many things can only be truly understood through personal experience.

Similarly, Feng is not as pessimistic now. In the past, he collected "toxic chicken soup" quotes and enjoyed signing his QQ profile with phrases like "Never work hard, because once you do, everyone will realize your true abilities are not that great."

But now, he has come to prefer sharing positive content. He said that immersing oneself and putting effort into something is not just about pursuing good results; rather, the act of "putting in effort" itself brings a tangible sense of life and immersive joy.

When reflecting on Dou Zhan Shen, Feng once lamented that he was not brave enough at the time. But now, I believe he and the entire Game Science team can be considered the bravest group of people in the Chinese gaming industry.

I’m sure that after playing the game, you’ve noticed how the transformations that Dou Zhan Shen failed to achieve and the abrupt chapter transitions have all been compensated for in Black Myth: Wukong.

If you’ve read The Shepherd Boy's Fantastic Journey, you might believe that each of us has our own destiny, but not everyone can find it.

Like many others, Game Science experienced confusion and failure during the Dou Zhan Shen period, and they have created knock-offs and mobile games. Perhaps it is precisely these seemingly painful and helpless experiences that strengthened their commitment to their destiny.

Destiny is not merely a philosophical idea that what is meant to happen will happen, and what is not meant to happen should not be forced. It is not an unthinking desire or an unattainable fantasy; it is something that you are willing to reject all excuses for, exhausting every effort and shedding blood and tears, just to get a little closer to it. You always believe that destiny will ultimately be realized—if it hasn’t been realized yet, it must be because you haven’t given your all.

Looking back at the development of Black Myth: Wukong, Feng summarized it in three words:

"Let’s give it a try":

"Let’s try what others did flawlessly a decade ago, while we struggled to grasp the essence.

Let’s try to engage in discussions that are exciting but result in awkwardly low-quality production.Let’s try to boast in promotional videos with demos, only to find the actual performance lacking or the gameplay rather uninteresting.Let’s try to invest a lot of time in trial and error, overly confident or caught up in the moment, but repeatedly hitting walls, despite everything looking beautiful on the surface.The black monkey might be too lucky; it has been filled with challenges since its inception, and naturally, it is not without its regrets.When writing the script for the first promotional video, I had no idea how to turn this video into a playable level.When completing the first level for internal testing, I was unaware of the enormous cost of transforming the entire story into such levels.Even with what appeared to be a complete story, I still didn't understand what it meant to make it stable, smooth, compatible with various hardware and software platforms, and translate it into over a dozen languages, and then release physical copies and discs.Not knowing is actually good.Since we've chosen to dance in the no-man's land, we must embrace the fear and anxiety that come with uncertainty. Because behind fear and anxiety lies the joy of satisfying curiosity and the pleasure of self-discovery.In this unknown fog, our only guide is to ask ourselves and every team member more questions:Is what we are doing now something that we, as users, understand, recognize, and love?Have others in the world faced the challenges we are encountering now? Even if no one has, can we do it?If the answers to the above questions are all affirmative, then it’s certainly worth trying."

Fortunately, they ultimately overcame obstacles and achieved greatness.

This long journey to obtain the scriptures proves to the world that as long as you are willing to embark on the path to the West for what you seek, vanquish demons and eliminate evils, you will surely attain the true scriptures in the end. Perhaps this is what moves and inspires all game developers—the belief that we must believe, even if it sounds overly idealistic or even childish.

As we endure through 81 challenges, may we all hold courage in our hearts, face our destinies head-on, until we finally reach the Ling Mountain.